Pro Take: Kickstarting IPOs of Venture-Backed Companies Will Probably Take More Than One Blockbuster Debut

Before risking an initial public offering, many late-stage startups that raised capital with high-priced shares at the height of the venture-investing boom two years ago need more time to build their businesses to levels that justify towering valuations, investors and market analysts say.

Reopening the IPO market for hundreds of billion-dollar startups waiting in the wings will also require a lot of unwilling investors to accept losses on pricey shares in companies whose current valuations are simply out of reach, they say.

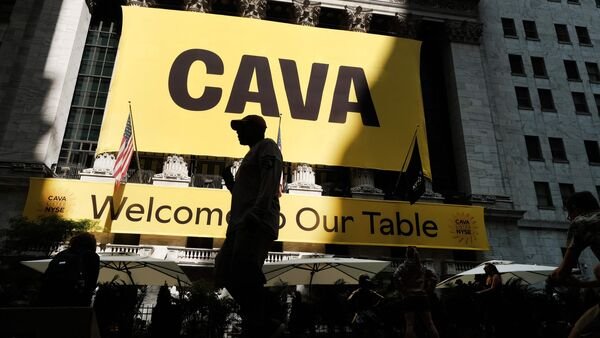

Cava’s venture investors may have fared well this week, but one strong public debut might not signal the good times are back for IPOs, though it may prompt other startups—and their investors—to test the waters.

A recent tech-market rally could also make a public listing more enticing than it appeared just weeks ago.

Launched in 2006, the venture-backed Mediterranean restaurant-chain operator on Thursday sold more than 14 million shares on the New York Stock Exchange, raising $318 million under the symbol “CAVA.” With its stock price opening at $42 a share, the Washington, D.C.-based company’s valuation climbed to $4.9 billion. On Wednesday, Cava, whose past investors include Invus Group, Declaration Partners and Legend Venture Partners, had set its opening price at $22 a share at a $2.5 billion valuation.

Cava operates more than 250 restaurants across the U.S. In May, it reported $564 million in sales for 2022, and a net loss of $59 million, according to a securities filing. As of mid-April, it had $203 million in sales, up 28% from the same period last year, and a net loss of $2 million, the company said.

Cava’s public debut performance will be welcome news for late-stage startups that postponed IPOs over the past year, citing unfavorable market conditions, rising interest rates and economic uncertainties.

But its immediate impact on the tech IPO market is expected to be offset by a more deep-rooted cause of the yearlong drought in new listings: the 2021 venture-investing bubble, which analysts say will take another year or so to work through.

Growing into high valuations, by boosting revenue to a point where it reflects a more accurate measure of a startup’s real worth, is going to take time—if it can be done at all. That is especially true for enterprise-technology startups, where sales growth hinges on corporate customers who typically move at a much slower pace than consumers.

Fraser Thorne, chief executive of investment research and investor relations firm Edison Group, said the poor stock-market performance of high-valued startups that had public-market debuts at the height of 2021 “has certainly caused a reappraisal of listing valuations for aspiring companies.” By Edison’s tracking, the overwhelming majority of 2021 IPOs have been trading significantly below their issue price, Thorne said.

“This is something new IPOs will want to avoid, which explains some of the current caution,” he said. “A disastrous IPO will get your name out there, but potentially have negative effects on your attractiveness for an investor audience.”

A startup’s ability to generate revenue is a key factor in setting its share price for an IPO. But equally important, analysts say, is the size of its valuation in relation to revenue or sales, and how that compares with private- and public-market competitors.

Revenue multiples, for instance, gauge the value of a startup’s equity price relative to sales. Low multiples reflect cheap, or undervalued startups, while higher multiples may indicate a startup’s shares are overpriced. For startups that were raising piles of cash in 2021, when near-zero interest rates helped fuel a surge in private-market investing, towering valuations today don’t necessarily reflect runaway sales growth or profit.

Market analytics firm PitchBook Data says there is a backlog of about 240 startups globally that should have gone public by now, based on invested capital and historical data. Kyle Stanford, senior analyst and U.S. venture lead at PitchBook, said most of these companies are now working to earn their valuations—though some may never achieve it—through revenue and profitability, to stand a better chance of avoiding a lackluster IPO or a reputation-destroying down funding round.

“Right now, we are seeing the bubble in enterprise tech startups pop in slow motion,” said Rami Cassis, chief executive of Parabellum Investments, a family office operating as a private-equity firm.

To their credit, some of the world’s biggest startups are taking a hit now, rather than later. Stripe, a digital payments startup, in March said it raised more than $6.5 billion in a Series I funding round that valued the 13-year-old Dublin company at $50 billion. That is a far cry from its peak valuation in March 2021, when Stripe said it raised $600 million in a funding round that valued the company at $95 billion.

Jody Foldesy, managing director and senior partner at Boston Consulting Group, said many startups that thought they would have gone public by now are instead realizing they need to batten down the hatches for the next two or three years to avoid a down round.

Rather than racing to a quick IPO, Foldesy is advising startups to better control the amount of cash they burn through between funding rounds and, in some cases, make their operations more professional.

“Improvements across these areas help justify higher valuations ahead of these sales down the line,” he said.

Write to Angus Loten at Angus.Loten@wsj.com